Nothing is more persuasive than the illusion of reasoning

The answer must be in here somewhere

I have been working with ChatGPT to learn about how Large Language Models (LLMs, which include Claude and Gemini) work, and then on how to use them effectively. I was worried that ChatGPT wouldn’t be particularly good at this, particularly since human beings are so poor at explaining their own motivations to themselves.

We have trouble explaining ourselves to ourselves.

Rather, humans are good at explaining their motivations; it’s just that they are not that accurate. It’s not because we just lie to ourselves, though sometimes we do—often these assessments are pretty good. It’s just that we don’t have privileged access to our own underlying motivations.

It’s kind of the same way we can do a pretty good job of explaining the specific motivation of someone we know well when they make a decision, or respond in a certain way to a situation. We are always in our own company, and have watched ourselves make all sorts of decisions and acted in all sorts of ways, and know how we felt about those decisions and actions afterward. But we don’t perceive our own motivations directly.

Check your own revealed preferences to better understand yourself

It took me some years to realize that I didn’t know specifically what kind of woman I was attracted to—I just had to look at who I was and had been attracted to, and examine the regularities and the differences. This is true of a lot of things, but who you are attracted to has high visibility and has significant consequences on your happiness and life path, and so is an important choice. Sometimes you might recognize that what you are attracted to, in a mate, a choice of job, or who to hang out with, has bad long-term effects, and then have to work with a motivation system that you feel is not serving your long-term needs well.

But ChatGPT has no inner life. All it has are weights and tokens derived from a massive amount of linguistic training data. And that training data has a lot of examples of how to train, as well as a lot of content on LLMs themselves.

Why LLMs can seem to reason

So far it’s been doing a good job of teaching me, though I am early on in the roughly six-month initial training program it has suggested to me.

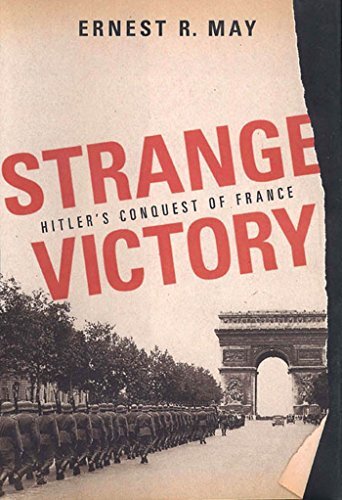

One key point is that LLMs don’t reason. They have incorporated vast amounts of written reasoning, and use those sequences to generate what looks very much like reasoning, but definitely isn’t. It explains where reasoning-like behavior comes from, even if there is no actual reasoning:

A token is plausible because it fits learned patterns, not because it is valid or true. Reasoning‑like behavior is imitation of structural constraints, not inference.

As it happens, I have been working my way through a book on reasoning and inference: The Enigma of Reason (2017), by Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber. There are a lot of opinions in cognitive psychology and philosophy about reason, and they try to provide a context for their own positions by referencing both those researchers and thinkers they agree with and those they don’t, and why.

I find that comforting. But should I? Could an LLM produce a book that is just as persuasive, but misleading in some way?

Mercier and Sperber have already hit on the point in their chapter on “Metarepresentations”, and why we find explanations persuasive.

We have clear intuitions about the “goodness” of various explanations. As the psychologist Frank Keil and his colleagues have shown, these intuitions may not be very reliable when they concern our own ability to provide explanations…We are, however, better at evaluating the explanations given by others. Even children are typically quite adept at recognizing the expertise of others in specific domains of explanation, and at taking advantage of it.

Mercier and Sperber see a variety of lower-level modules in our thinking and responses, a model of the brain and mind I have long found persuasive. But because we don’t have any privileged access to the internals of those modules, we can be spoofed without realizing it. How does this particular module respond to the reasoning-like explanations of an LLM?

I feel that I have a sense of when someone has done the work and seems to understand what they are explaining to me. In fact, explaining something to someone else is a good way to see if we understand it ourselves, another example of how we sometimes need to move outside ourselves and then go back in to get a better idea of what we actually know, think, and feel.

Fake images, fake videos…fake explanations?

Most of us have at some point donned some off-the-rack explanatory reasoning to hide our own cognitive nakedness. We expected someone else to find that reasoning persuasive, when it was not that reasoning that gave us the position we hold.

It’s clear that it doesn’t take LLMs to flood that explanation-validating module into uselessness. Our general online cognitive environment has already done that. But LLMs may supercharge it.

The best way to defend ourselves might be to use our feeble reasoning powers to provide that sensitive module with some input hygiene, some rule like “don’t put anything in your brain that you wouldn't put on paper”. But reasoning is feeble and easily worn out, as well as frequently misapplied. We do need to learn how to defend ourselves.

I read Mercier and Sperber last night, and worked with ChatGPT this morning. Clearly, the topic is on my mind. Still, the fact that ChatGPT explained to me the possible implications of what Mercier and Sperber had been thinking indicates that I may be right to focus on these concepts.

What revealed preferences have you found in your own life?

What other ways have you found to understand your own motivations?