On The Inappropriate Disposal of Coffee

I was recently struck by a story in The Guardian, about a woman in west London, Burcu Yesilyurt, who was initially fined £150 for pouring out what was left in her takeout coffee cup before getting on the bus, presumably to get to work.

The kind of thing we never used to know, or care about

Doing so violates section 33 of the Environmental Protection Act 1990, which is mostly about disposal on land, but does have the covering statement “a person shall not…treat, treat, keep or dispose of controlled waste (or extractive waste) in a manner likely to cause pollution of the environment or harm to human health.” The bolded phrase is what was cited as justification for the fine.

They told her she should have poured the coffee into a disposal bin. I generally dislike doing this because it leaves a giant, sloshy mess, and in places where actual humans have to pull out the bags and haul them somewhere, it makes their job even less pleasant than it already is.

How absurd is a fine for pouring out coffee, anyway?

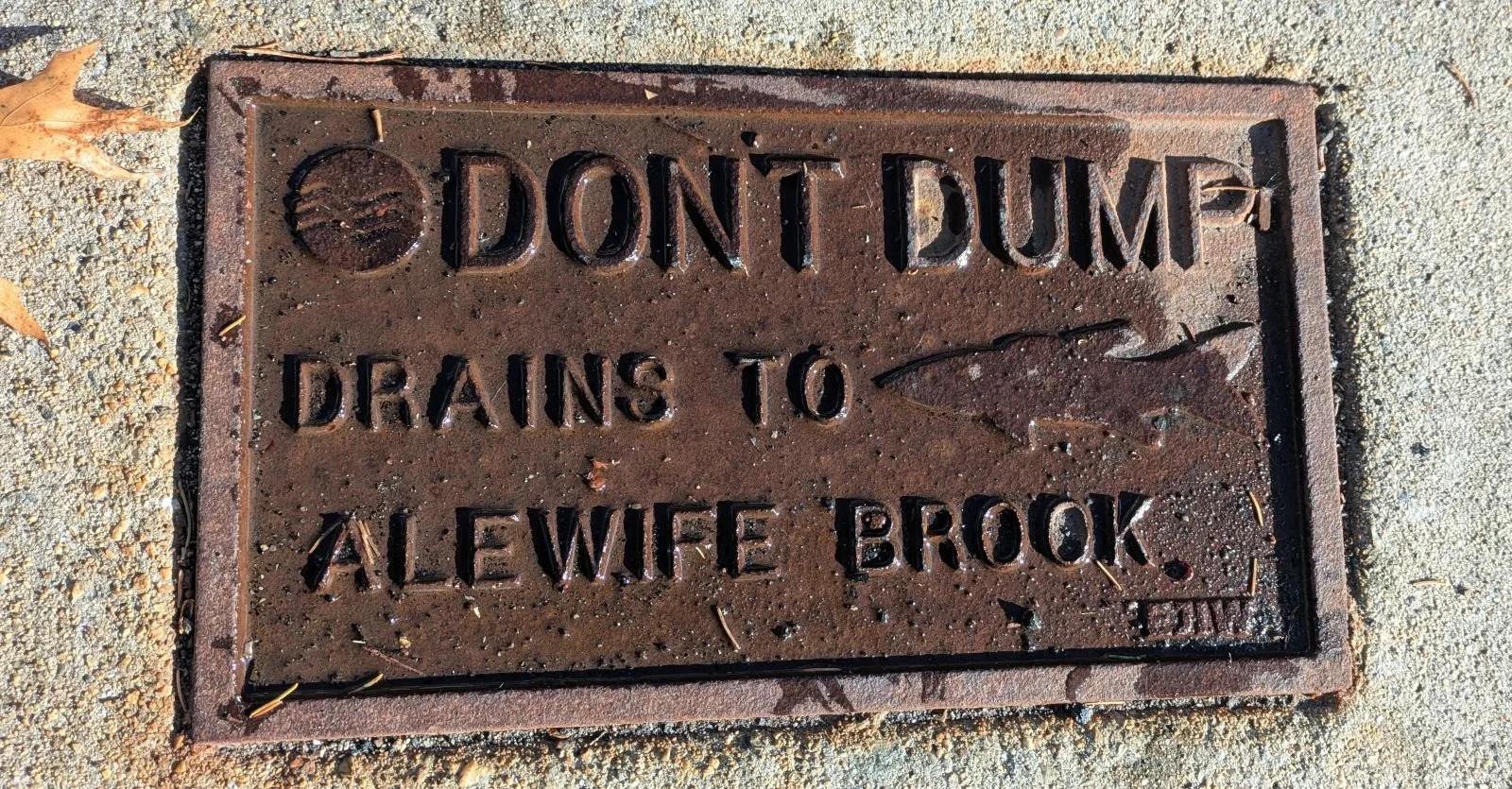

So, I initially thought the whole thing was ridiculous. But a bit of looking around (with the help of ChatGPT 5.1) indicates that coffee, and particularly its caffeine, is an actual hazardous substance, particularly when poured into storm drains that pour unprocessed into rivers, lakes, or the sea. Even if it is poured down the sink, most waste processing doesn’t get rid of caffeine.

The volumetrics of unused coffee disposal is a shockingly understudied topic, but clearly, everyone drinks a lot of coffee, and buys even more than they drink, so there is always a lot of coffee going down the drain. Though I suspect much of that volume is from places that brew coffee and have to get rid of old coffee, because if they tried to sell it, they’d quickly have no business.

Fresh hot coffee at any time is one of the wonders of modern civilization. But, like most of the rest of our luxuries-turned-necessities, it comes with environmental externalities.

The environmental impact of staying awake in Sweden

Rosa Hellman, of the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, wrote a Master’s thesis (PDF) on liquid coffee waste in food-service settings. She estimated that Swedish restaurants and cafés discard something like 17,000 to 25,000 tonnes (that’s metric tons, 10 percent bigger than US tons) a year.

Hellman also cites a food diary study by the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, which found that in 2020, households disposed of 190,000 tonnes of food and beverages through sewage, and 45 percent of that was coffee or tea. That works out to around 8 liters per person per year of coffee and tea, not separated in the study.

The restaurant and the food diary numbers are about two quite different things, so they can’t be combined to give a good estimate of how much coffee is getting into the water.

What’s the appropriate fine for inappropriate coffee disposal?

Ms. Yesilyurt felt that £150 was a bit steep, and I’d have to agree. The fines in the now-notorious section 33 seem aimed at businesses and other larger operations, not individuals getting rid of whatever is left in their takeout (well, this is London, so “takeaway”) cups. £150 is the minimum amount stated.

Interestingly, the Guardian article didn’t bother to tell us how often anyone in the UK gets fined for inappropriately disposing of coffee. I can’t find any source of information. Was Ms. Yesilyurt the first person in the UK ever hit with this fine? After she made an issue of it, they rescinded the fine, which seems to be the way these things always work.

The article does add a bit of back and forth over whether the cops were too aggressive, but that seems mostly because anyone confronted by three police officers and given a significant fine after doing what Ms. Yesilyurt did would be startled and nervous. Though this does stimulate the usual harrumphish but not inappropriate question: “Isn’t there some actual crime you people should be preventing or solving?”

What made them decide to do this? Ms. Yesilyurt seems a demure sort, not dangerous or likely to be aggressive, so maybe she was just an easy target at that time of day.

Who should bear the cost of preventing environmental damage?

Every action has an environmental consequence, but when is it worth tying that consequence to the small daily actions of individuals? A fine commensurate with the actual impact would be too small to be worth levying. And if cafés then have to bear the burden of undrunk coffee somehow, that makes it marginally less appealing to run such a business, and we like to have our cafés on every corner. Who is the lowest cost avoider here?

How well would you, bleary-eyed and about to get on a bus to get to work, have reacted in this situation?